Outdoor writer Doug Peacock speaks at Whitefish Review event

Peacock shares stories of a life in the wild

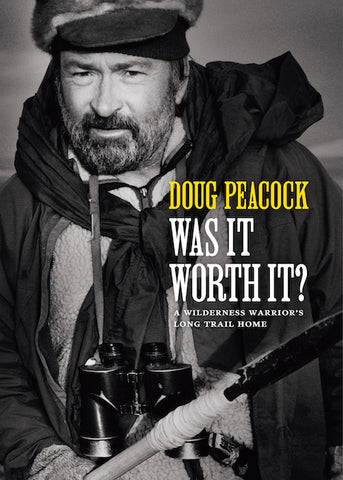

Whitefish Review will present a reading and discussion with author Doug Peacock on Sept. 23, reading selections from his new book, 'Was it Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home.'

Peacock, an author, Vietnam veteran, filmmaker, and naturalist, has published widely on wilderness issues. Peacock was a Green Beret medic and the real-life model for Edward Abbey’s George Washington Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang. Peacock is best known for his book Grizzly Years: In Search of the American Wilderness, a memoir of his time observing grizzly bears in the western U.S. in the 1970s and ‘80s.

In this new collection of gripping stories of adventure, Peacock reflects on a life lived in the wild, asking the question many ask in their twilight years: “Was It Worth It?”

Recounting sojourns with Abbey, but also Peter Matthiessen, Doug Tompkins, Jim Harrison, Yvon Chouinard and others, Peacock observes that what he calls “solitary walks” were the greatest currency he and his buddies ever shared. He asserts that “solitude is the deepest well I have encountered in this life,” and the introspection it affords has made him who he is: a lifelong protector of the wilderness and its many awe-inspiring inhabitants.

The event is at Casey's in downtown Whitefish, Montana, 101 Central Avenue. Doors open at 6:30 pm with live music by local singer/songwriter David Walburn and legendary local multi-instrumentalist and slide guitarist, Michael Atherton.

Walburn recently released his sixth CD, “My Embrace,” a collection of fifteen songs, all written and recorded in David’s home studio in Whitefish, Montana. Readings and Q/A begin at 7:30 pm with Doug and editors of Whitefish Review. Book signing and more music will conclude the evening from 8:30 to 9:30 pm.

A $10 entry donation is suggested to support the non-profit journal. For more information, visit www.whitefishreview.org.

From his latest book

The following is from Doug Peacock’s new book, Was it Worth It: A Wilderness Warrior's Long Trail Home (Patagonia Books, 2022).

The current pandemic will not be our last plague and it is a prime symptom that our center is not holding. Our smug assumptions of the primacy of our civilization are coming apart. Humans are not in control of the world we live in. We are not in charge.

Wildfire is everywhere, burning trees and releasing record carbon emissions: the boreal forests across Siberia and Alaska, the criminal fires in the Amazon, the fires of denial in Australia, and the unstoppable fires in our own Lower 48.

Related are rising temperatures in grain-producing regions of the world, mainly North America and Asia. These crops could fail any season now, resulting in worldwide famine. Starving people would want to get the hell out, go someplace north where they could grow food. Since humans occupy virtually every fertile chunk of ground on Earth, conflict is unavoidable. Wars will break out. Along with pestilence, this sounds like a warning from the New Testament.

Cattle are a worldwide curse. Besides the methane they produce, cows are an excuse for burning the Amazon, the loss of which, many think, will be the tipping point for the global carbon exchange keeping the planet alive.

We have not told ourselves the truth. Because it was everyone’s job, it was no one’s job.

There is so much beauty in the world; all we have to do is stick around to see it.

For a father who loves the Earth and finds joy in defending wild landscapes, considering our demise as a species is not a pleasant exercise. But we need to see the truth, the raw, unvarnished truth. Science and journalism water down the severity of a changing climate and pull their punches. When we try to extract the most credible science from each, we find much of it filtered through caution and timidity. There are semantic arguments that optimism and hope will color a rosier world, but how we feel about it does not change that unpolished truth.

What about temperatures too hot for life on Earth? Or habitats too impaired for survival? Some places on Earth like Australia are approaching 1.5 degrees Celsius above baseline, and the Arctic is 5 degrees above. The highest temperature modern humans have ever experienced over 315,000 years on Earth is about 3.3 degrees Celsius above baseline, much higher and human survival on this planet will resemble an experiment in a caged-rat lab.

“That which evolves does not persist without the conditions of its genesis” is a sentence I’ve found myself repeating monotonously throughout the decades. When I first wrote that line in a Glacier National Park fire lookout in the 1970s, I was thinking about habitat, especially grizzly bear and human habitat, which I considered the same—the mingled fates of humans and bears.

For the first three hundred thousand years of our time on Earth, human intelligence was carved in habitats whose remnants today we would call wilderness. Only in the past fifteen thousand years have we modified that wilderness, first with the extinction of the great late Pleistocene megafauna, and then with the rise of agriculture from multiple origins around the globe in the last ten thousand years. For over 95 percent of our time on Earth, human evolution, organic intellectual evolution, was honed in that preagricultural landscape, owing little or nothing to our time on farms or in cities. That relationship is something I don’t want to gamble on—the fight to preserve wilderness is still primary.

That late Pleistocene megafauna extinction in North America was the result of climate change (the Pleistocene warming pales in comparison to the rising heat today) combined with human activity, namely overhunting, around fourteen to sixteen thousand years ago. This is the same deadly duo threatening us today—climate change and the destructive lie of endless economic growth on a planet with finite resources.

The temperature (the Bølling-Allerød warming lasted from 14,700 until about 12,700 years ago) had been rising since about 20,000 years ago and the hunters were called Clovis people. The Clovis, known by their characteristic spearpoints and a Montana child-burial, arrived in the Lower 48 a little more than 13,000 years ago. Seafaring people likely arrived south of the ice via the northwest coast maybe 14,500 years ago, but there is no evidence they had a visible impact on the land or even survived to meet up with Clovis.

The Clovis big-game hunters, whose distinctive technology was probably developed south of the ice, came down the ice-free corridor from Alaska, as evidenced by elk-antler tools. Elk came across from Siberia around 14,700 years ago and then waited for the corridor to melt and grow sufficient vegetation to support their migration south. They certainly didn’t swim down the coast. Elk apparently preceded the Clovis people by hundreds of years; why the Clovis people waited so long to come down (they could have survived in the periglacial narrows by waterfowl hunting and by packing pemmican with dogs before the corridor was vegetated) is a mystery.

I suspect an abundance of Pleistocene lions, big saber-toothed cats, and short-faced bears. But the Clovis successfully exploded across North America, and in a few hundred years, left their fluted projectile points all over the land, including at a dozen or so mammoth kill sites. Had lots of scavenging, short-faced bears been around, it would have been very hard to secure a mammoth kill on open ground. Then they were gone, not the people but their way of life, in just several hundred years. Many large species of American mammals disappeared with Clovis. I record this period with envy: I can’t imagine a more vibrant time to be alive in North America.

When it is indeed our time to walk offstage with the mammoths, what might be the measure of our character at the end of our tour? After peering into the abyss, how do we behave? There is great joy in doing the toil of the world, fighting for wild causes, saving pieces of the magnificent natural world.

There’s plenty of work; do your job with decency and an open heart. Love your brothers and sisters in all actions, in all relationships. Speak the truth. Extend your innate empathy to distant tribes and strange animals. Arm yourself with friendship and love the Earth. Remember your elders: Walt Whitman said, “Resist much, obey little.” Or, as Ed Abbey noted, “A patriot must always be ready to defend his country against his government.” Hold nothing back. Join the tribes in their dignified defense of Native rights: An Indigenous viewpoint should replace all notions of Western wildlife management. Respect this militant fresistance and embrace the necessity of civil disobedience. What’s right isn’t always legal and vice versa. Consider getting arrested.

Who and what is at risk? If past extinctions provide guidelines, then it’s all life larger than a small meadow mouse. Now I can unpleasantly anticipate being among those minority humans left on Earth to die from old age. I’d be happier if everyone could. It’s the scourge of my geezer-hood; I am unconcerned with my own death and fatally engaged in the lives of all my survivors. There’s a bottomless, contradictory sadness in a fleeting glimpse of justice—nature bats last avenging the scorched Earth, payback to Homo sapiens—bundled up in the loss of beauty and suffering in the lives of the people you love most.

Leave a comment