Montana housing prices: How we got where we are

Photo by David Reese/Montana Living

Montana communities grapple with solutions to affordable housing

By Patrick Barkey/Montana Business Quarterly

After rising faster than incomes for seven consecutive years, Montana home prices took a sudden and surprising jump across Montana in the wake of the pandemic outbreak, pressing affordability for buyers in some areas to the breaking point.

Forecasters spend a lot of time analyzing trends in data for a simple reason: Those trends form the foundation of their projections. And for buyers, the trends in housing prices are alarming.

So, the question becomes, what lies ahead?

The price of housing, like most goods and services, depends on the interaction of supply and demand in each regional market. But there are many unique aspects of housing that lie behind those familiar concepts. Since new housing takes time to plan, develop and build, surges in demand, like what we saw in late 2020 through 2021, are reflected mostly in prices.

Since housing is expensive, housing purchases are usually financed with borrowed money, making interest rates a critical factor for demand. And those rates have been very low for several years.

But housing’s uniqueness in our economy goes much further than that. Shelter is a basic human need, and economic and political systems that fail to house their populations are judged as failures. That fact no doubt accounts for what is possibly the most unique aspect of housing, and that is the dozens of policies and regulations imposed by governments at all levels that support, modify and in many cases restrict its production. The future of housing depends critically on the future of those policies as well.

Photo by David Reese/Montana Living

Market Responses to Higher Demand

The COVID-19 pandemic served up plenty of surprises, but few were bigger than what happened to housing markets.

The Great Recession of 2007-09 hammered real estate markets, but the COVID-19 recession did just the opposite. After a March and April 2020 period when the economy froze, buyers emerged with a new desire for residential space that surged across regional markets that were already supply constrained. The result was an acceleration in housing prices in almost every market in Montana.

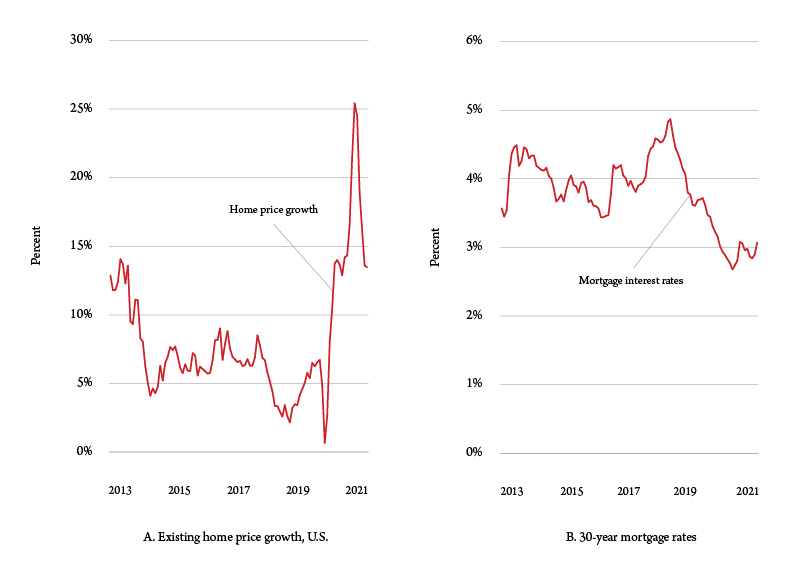

As shown in Figure 1a, price growth that was averaging about 7% per year in the nation as a whole between 2013 and 2019 surged up to a stunning 23.6% annual rate in the summer of 2021. In some markets, price growth was even higher.

Gallatin County median sale prices were just under $700,000 in 2021, up 30 percent.

Figure 1. Home price growth and mortgage rates. Sources: Redfin and Freddie Mac.

Figure 1. Home price growth and mortgage rates. Sources: Redfin and Freddie Mac.

No one predicted this outcome, yet in hindsight it is easy to see some of the forces that combined to bring it about. These factors of Montana's rising home prices include:

-

The quick adaptation of the real estate industry to social distancing, using video showings and e-closings that effectively widened the market to a national pool of potential buyers.

-

The quick transformation of what had been a slower affordability migration from higher priced states to places like Montana to an accelerated surge as physical space needs and crime concerns changed attitudes about density in major cities.

-

The reluctance of sellers to list their homes, either out of fear of contagion or concern that the supply of housing to serve their changed needs would be inadequate.

-

The decline of having to work in offices and the rising incidence of working from home and its impact on space needs.

Yet there were two more familiar and arguably more impactful forces that helped propel housing demand and housing prices to stratospheric heights in 2021 – mortgage rates and income.

As Figure 1b makes clear, conventional 30-year mortgage rates fell below 3% at the same time as prices were surging. And unlike previous recessions, the COVID-19 recession saw heady increases in consumer incomes.

But mortgage rates are about to move up as Federal Reserve policy finally reacts to higher inflation across the economy – and the impacts on housing demand could be profound. Real estate brokerage Redfin is predicting that higher mortgage rates will produce much slower price growth nationally by 2023.

Policy Responses to Housing Affordability Declines

Housing markets are ultimately local, even if national forces affect them. The effects of high prices have been felt locally, giving rise to everything from long distance commutes to people living in RV parks in some Montana markets. And local governments impose a complex, overlapping web of building codes, zoning classifications, development and impact fees, and other policies that collectively impact how much, what kind and what places housing is built. As the evidence that slow building rates affect affordability mounts, is there any likelihood of a reexamination of those policies?

Policy actions clearly have impacts on markets, but the process that sustains or possibly modifies them is essentially political. Here we must squarely confront the less remarked upon fact that superheated housing markets in Montana, as elsewhere, have created winners, primarily existing homeowners who avoid disruptions in their neighborhoods as their housing wealth skyrockets.

The median voter hypothesis is a simple idea which holds that in a democratic government, it is the view of the voter squarely in the middle of the distribution of viewpoints on any given issue that prevails. And research says that many of the local policies that restrict housing supply, such as single-family home zoning, parking space requirements and building codes mandating things like windows in bedrooms are quite popular. Even those who are shut out of neighborhoods because they can’t afford to live in them say that they would prefer to live in older neighborhoods with tree-lined streets and backyards.

Yet if policies affect prices, perhaps the inverse may someday be true as well. Markets are producing outcomes in some local housing markets that threaten to transform communities, pushing those who work in service jobs to the periphery as those with the means to afford housing – and consume many of those services – enjoy what their policies preserve.

— This article is rebroadcast with permission from Montana Business Quarterly

How one county is tackling affordable housing in Montana

In Gallatin County, officials are working with the local community to create affordable housing.

With its rapid growth rate, Gallatin County is experiencing difficulties with housing availability for employees. This pertains to both employees seeking to move to the community as well as employees who need to transition into a different housing arrangement.

The county is proposing to create affordable housing on land the county owns in Bozeman. Gallatin County is also seeking 3-year lease with a potential for renewal for residential units for primary use as county employee housing. The facilities will primarily be sublet to current county employees and local employees with an impending start date.

The quantity of need is unknown, but the county anticipates beginning the program with approximately six units, according to the county. The units would accommodate a mix of one to three bedrooms. Multiple proposers may be necessary to fulfill the request; owners with only one type of unit or less than six units are welcome to respond. The county will be the tenant and will independently manage sublets.

Montana’s Unaffordable Housing Crisis

by

The lack of affordable housing has been an increasingly difficult problem for many Montana communities. With relatively few affordable homes available for households earning a low income, and with much of the existing affordable inventory aging and in need of rehabilitation, many households earning a low income are being priced out of housing markets.

When households become highly cost burdened they experience many difficulties in regard to health and well-being outcomes. Those households priced completely out of the market experience the unending difficulties associated with homelessness.

And it is not merely the cost-burdened household members who suffer. The difficulties of being cost-burdened or homeless extend from the individuals directly involved to the communities where they live. This imposes costs on community hospitals, schools, criminal justice efforts, infrastructure upkeep and many other community institutions. Reducing these costs will be an increasingly pressing problem moving forward.

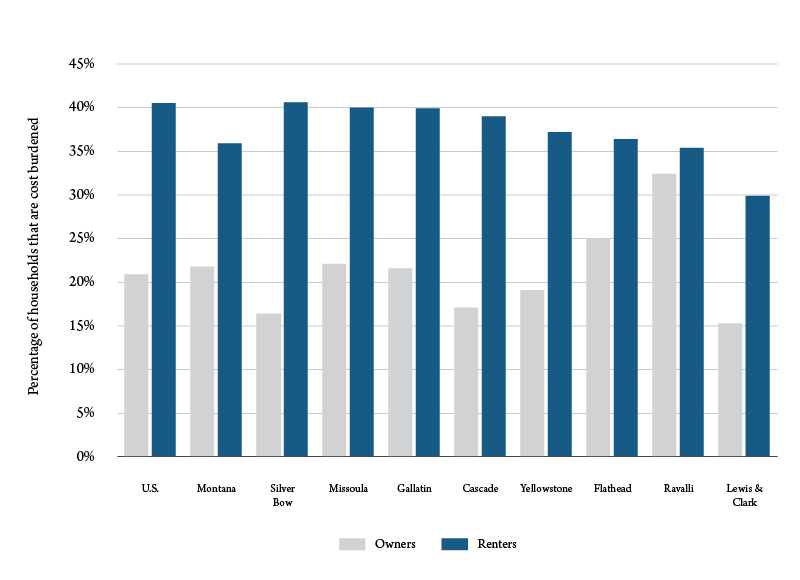

Figure 1 shows the extent of cost burden among renters and homeowners in various counties in Montana, and compares that to national and statewide averages.

Demand for affordable housing in Montana far outstrips supply. For example, statewide there are only 39 affordable housing units for every 100 households earning an extremely low income (below 30% of area median income). Since 2016, there have been over 30,000 applications for housing choice vouchers, with only about 4,000 issued. This indicates a demand-supply ratio of more than 7-to-1 for this program alone.

In order to understand the impacts of housing affordability challenges, it is helpful to consider the situation of complete unaffordability – homelessness. The costs borne by homeless individuals and families are stark and clearly visible. The instability caused by homelessness turns many basic necessities into near impossibilities. Finding adequate food, shelter, clothing, washing facilities, transportation, health care, education, personal safety and security, and employment become highly time-intensive and often impossible. These challenges are compounded by the high levels of substance abuse and mental illness experienced by homeless individuals and families.

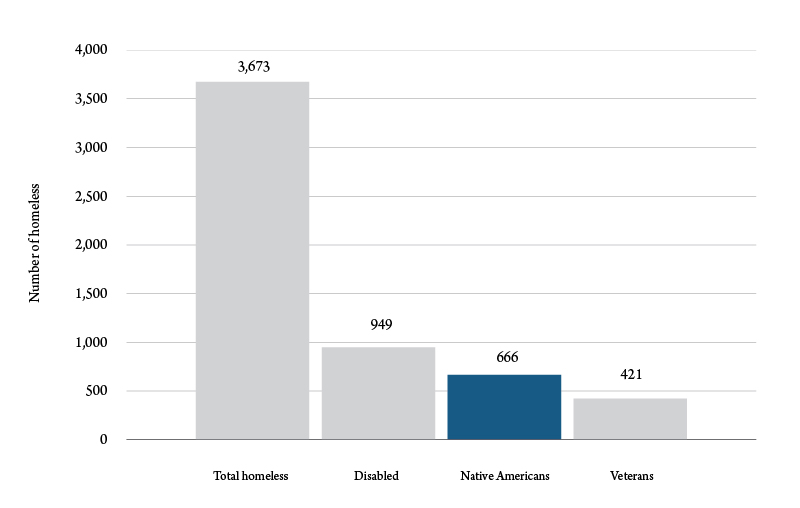

Figure 2 shows an estimate of the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in Montana. The proportion of Native Americans experiencing homelessness in Montana is noteworthy. It is estimated that Native Americans make up 6.5% of the population of Montana, yet individuals identifying as Native American make up 18% of the total homeless population. This constitutes an almost three times overrepresentation in the data.

Over the past several years affordable housing has become a nationwide concern. Prior to 2020, we had record lows in unemployment, record highs in the stock market, but troubling increases in income inequality. This had been a cause of growing concern, particularly in the area of housing where the cost of rent had been rising faster than wages in most areas of the United States. The year 2020 exacerbated these concerns by adding record unemployment claims and record business closures, on top of continuously rising housing costs.

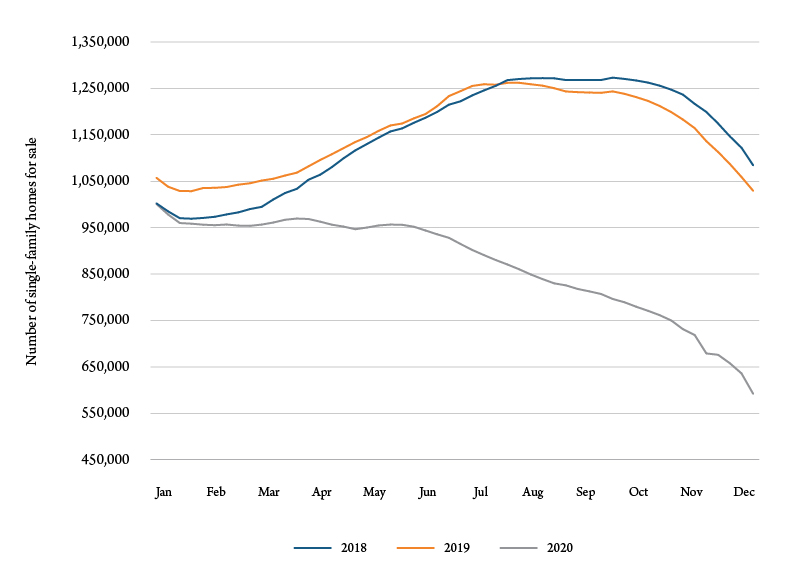

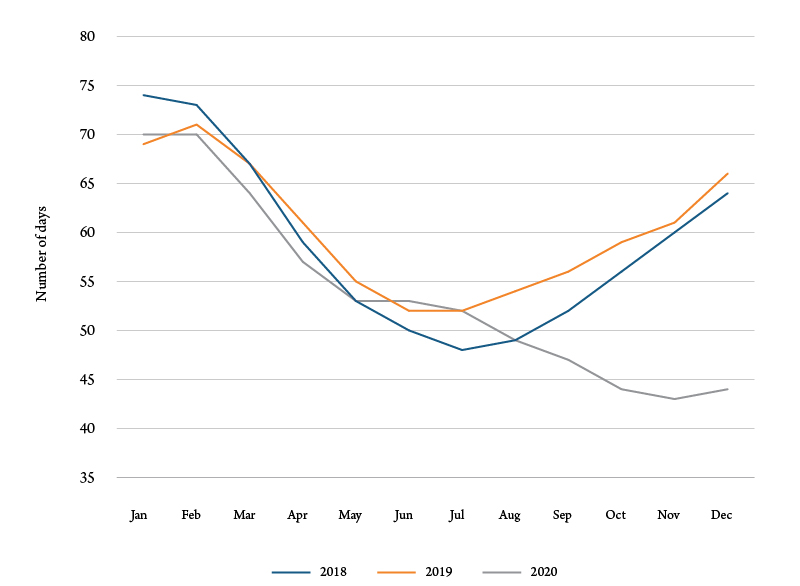

As with any market, housing prices are influenced by supply and demand factors. The current boom in home prices is no different. One of the starkest factors driving this trend is the lack of available housing supply in the United States. Figure 3 illustrates this phenomenon by showing the number of single-family homes available for sale throughout the calendar year in the U.S. for the years 2018-20. We see that historically there have been roughly 1 million homes for sale at the beginning of the calendar year. This number tends to rise through the spring and early summer, peak in late summer, and fall back to around 1 million by the end of the calendar year.

We see in Figure 3 that 2020 was a major deviation from this trend. While the year started with the same number of homes for sale as in previous years, the housing inventory did not rise through the spring, and started falling precipitously through the summer and fall. The available supply of single-family homes for sale at the end of 2020 was little more than half of the inventory at the beginning of the year. As of January 2021, there were less than 576,000 available single-family homes for sale across the country.

The demand side is also driving the recent housing market boom. Figure 4 shows the average number of days a home is on the market before a sale is pending throughout the calendar year for the years 2018-20. Again, we can see a clear 2020 deviation in buyer behavior from previous years. We have vastly fewer homes for sale nationwide, and buyers are acting fast to make deals.

Communities are economically stronger, and are able to offer a shared, higher quality of life when there are employment opportunities for all who seek jobs and a variety of homes available for renting or buying. In situations like this, almost every household can find the home that fits their needs and their budget. In these communities, children are able to focus on school instead of the stress of homelessness, there are fewer or no food-insecure families, people can spend more time focusing on their own health, and people are able to plan and save for their retirement.

The United States is currently facing a shortage of affordable homes, and Montana is no exception. With relatively few affordable homes available for households earning a low income, and with much of the existing affordable inventory aging and in need of rehabilitation, many households earning a low income are being priced out of housing markets. We are now facing ever expanding economic challenges, and these issues and concerns are not going away or getting better.

When housing becomes unaffordable, it imposes costs on entire communities, but the most vulnerable in society bear the brunt of those costs. Housing affordability will likely be a challenge that Montanans continue to face in the coming years, and as such it deserves a place in public conversation.

Leave a comment